No More Excuses, Minnesota.

Let’s Teach Kids to Read.

Minnesota is falling behind in reading—while Mississippi is leading the way.

While Minnesota continues to struggle with abysmally low reading scores and persistent achievement gaps, Mississippi has implemented bold, research-driven reforms that are getting real results for kids. This site explains how Mississippi became a national model for literacy, what Minnesota is doing in response, and why successful implementation of the Minnesota’s READ Act is our best chance to catch up.

How Mississippi Became a National Leader in Literacy

“Mississippi has more kids in poverty, spends less per student, has similar class sizes and increased spending at roughly the same rate as Minnesota — yet they managed to improve outcomes for their kids significantly, while Minnesota made things worse. Why?”

As former Minneapolis Public Schools Superintendent Peter Hutchinson pointed out in a recent commentary, over the past decade, Mississippi has transformed itself from one of the lowest-performing states in reading to one of the nation’s most improved. This didn’t happen by accident. Mississippi’s success is the result of deliberate, bipartisan policy decisions that aligned teacher preparation, curriculum, and classroom practice with the science of reading—the body of research that explains how children learn to read.

In 2013, Mississippi passed a sweeping literacy law that required:

State-approved, evidence-based reading curricula

Mandatory reading screening to identify K–3 students who are falling behind

Intensive professional development for teachers and school leaders

Literacy coaches in schools to support implementation

Retention requirements for 3rd graders who aren’t reading proficiently, paired with strong interventions

The state of Mississippi invested in teacher training, provided technical assistance to districts, and tracked outcomes closely. The result: Mississippi’s 4th grade reading scores on the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP, also known as “The Nation’s Report Card”) have steadily improved, surpassing national averages and outpacing Minnesota fourth-graders in most demographic groups. These gains have been especially strong among students of color and low-income students, demonstrating that equity and excellence can go hand-in-hand.

Mississippi is outpacing Minnesota in 4th-grade reading across all demographics, and continues to do so for Black and economically disadvantaged 8th-grade students.

Mississippi Spends Far Less Per Student than Minnesota, But Gets Better Results for Many Students

Perhaps most striking is that Mississippi is achieving these results while spending far less per student than Minnesota. According to NAEP data:

Mississippi spends $11,085 per student

Minnesota spends $15,327 per student

That’s over $4,000 more per student in Minnesota, yet many of our students are performing worse on national reading assessments.

As Chad Alederman writes in The74, “Mississippi is the poorest state in the country…but since 2013, the state has put in place a number of policy changes, including new curricular materials, a muscular school accountability system focused on the students who are the furthest behind and a third grade reading requirement that brought greater attention to children who struggle with the basics. Some of these initiatives even cost money, but they didn’t add up to that much relative to the state’s overall education budget, and they helped students in Mississippi leap over their peers in higher-spending states.”

This should serve as a wake-up call: spending more money won’t solve our literacy crisis unless it’s paired with focused, evidence-based policies and real accountability for results. Mississippi didn’t outspend us. They outworked us—and outsmarted us—on teacher training, curriculum, and implementation.

Minnesota is no longer a national leader when it comes to education. In fact, not only does the average Minnesota 8th-grade student perform below their peers nationally…

IMAGES CREDIT: EdAllies

… we continue to face enormous academic achievement and opportunity gaps between our white students and students of color…

… and between our low-income students and their wealthier peers.

Note: MCA stands for “Minnesota Comprehensive Assessment, the annual standardized test taken by Minnesota students beginning in 3rd grade.

“Mississippi is the poorest state in the country…but since 2013, the state has put in place a number of policy changes, including new curricular materials, a muscular school accountability system focused on the students who are the furthest behind and a third grade reading requirement that brought greater attention to children who struggle with the basics.”

Minnesota’s READ Act: A Promising Start, 10 Years Late

In 2023, Minnesota took a bold step—a decade after Mississippi—toward improving literacy by passing the READ Act (Reading to Ensure Academic Development Act). The legislation represents a major shift in how reading is taught across the state, with a clear goal: to ensure that every child receives instruction grounded in the science of reading.

What the READ Act Does

The READ Act requires all public school districts and charter schools in Minnesota to align their literacy instruction with evidence-based practices that have been proven to help children learn to read. These practices include structured, explicit teaching in phonemic awareness, phonics, vocabulary, fluency, and comprehension—core components supported by decades of reading research.

The law also requires:

Adoption of approved literacy curricula aligned with the science of reading

Statewide literacy screening to identify students who are at risk of falling behind

Ongoing professional development for teachers and school leaders

Literacy data reporting to track student progress and support decision-making

A statewide Literacy Center, housed within the Minnesota Department of Education, to support schools with training, technical assistance, and coaching

Want To Learn More?

Opinion: Mississippi and Louisiana improved reading scores. We in Minnesota haven’t — yet. By Peter Hutchinson on May 8, 2025 for the Minnesota Star Tribune.

How Do Kids in Top-Spending States Perform on NAEP? Not as Well as You’d Think. By Chad Alderman on July 29, 2025 for The74.

Sold a Story: How Teaching Kids to Read Went So Wrong. Podcast by Emily Hanford for APM Reports.

Minnesota—A State Where the Schools are Not Above Average. By David Schultz on July 21, 2024 for the Minneapolis Times.

There Really Was a ‘Mississippi Miracle’ in Reading. States Should Learn From It. By Chad Alderman on February 25, 2025 for The 74.

What Schools and Districts Are Expected to Do

Under the READ Act, districts must evaluate their current reading programs and materials and shift to state-approved options that align with research-based approaches. They are also expected to train all elementary teachers, including special education and English language teachers, in evidence-based literacy instruction. These changes must happen within a tight timeline, while schools are also navigating staffing shortages, budget pressures, and competing academic demands.

Concerns About READ Act Implementation

Passing the READ Act was an essential first step, but passing a law does not guarantee better outcomes for students. For Minnesota’s literacy crisis to be addressed, the law must be implemented with urgency, fidelity, and accountability. As with any major education reform, the real test is not what’s written in the law—it’s what happens in classrooms. But so far, implementation has been slow, inconsistent, and in some cases, met with resistance.

This means schools cannot solve this problem simply by purchasing new reading curriculum or materials. To see meaningful progress, schools and districts must train teachers well, monitor progress, and ensure that what’s happening in the classroom reflects what the law intends.

Some teachers have been hesitant to shift away from long-standing instructional methods, many of which are not aligned with the science of reading. This reluctance is understandable; teachers were often trained in programs that emphasized discredited reading strategies, and making a full transition to structured literacy takes time, support, and coaching. But without these changes, the law won’t deliver the outcomes it promises.

Many school districts have also been slow to adopt evidence-based literacy curricula, despite clear direction in the law to do so. While some districts have taken decisive action, others have delayed key decisions or continued using outdated materials. In part, this is due to the time it took for the Minnesota Department of Education to finalize a list of approved literacy programs.

Importantly, state and local leaders must be willing to measure what’s working—and what’s not—and make course corrections when needed. Without strong oversight, clear metrics for success, and real consequences for failure, Minnesota risks making the same mistakes that have kept reading scores flat for over a decade. Minnesota has the right law on the books; the READ Act gives us a once-in-a-generation opportunity to do better. But without stronger leadership, clearer timelines, and a greater sense of urgency at every level—from the Department of Education to the classroom—the READ Act risks becoming another well-intentioned policy that fails to improve results for students.

What Is the Science of Reading?

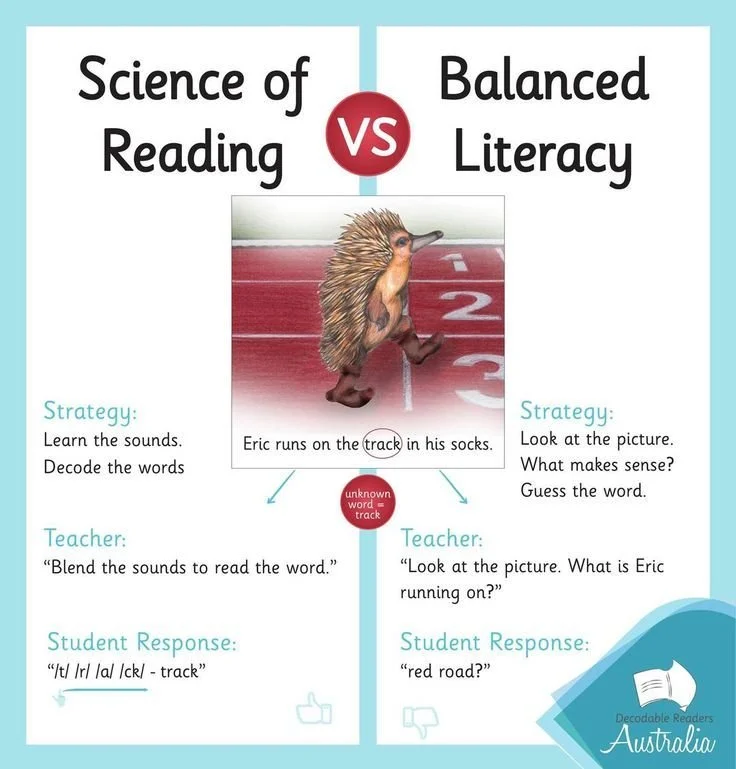

The science of reading refers to decades of interdisciplinary research on how children learn to read. This research overwhelmingly shows that reading is not a natural process—it must be taught through systematic, explicit instruction in phonemic awareness, phonics, vocabulary, fluency, and comprehension.

The above graphic shows the difference between a “Science of Reading” approach, which teaches students to learn the sounds that letters make and blend the sounds of those letters together to read a word (“track”). The “Whole Language” or “Balanced Literacy” approach teaches kids to make an educated guess at the word based on cues, such as looking at the picture.

IMAGE CREDIT: Decodable Readers Australia

Many schools have relied on outdated or disproven methods of reading instruction, leading to widespread reading struggles, even among students with strong potential. The science of reading offers a clear, proven path to help all students succeed.

Even though scientific research has shown how children learn to read and how they should be taught, too many districts, schools, and classrooms across Minnesota use “whole language” or “balanced literacy” English Language Arts (ELA) curriculums, which ignore decades of research and do not include nearly enough explicit phonics instruction to ensure all students become strong readers.

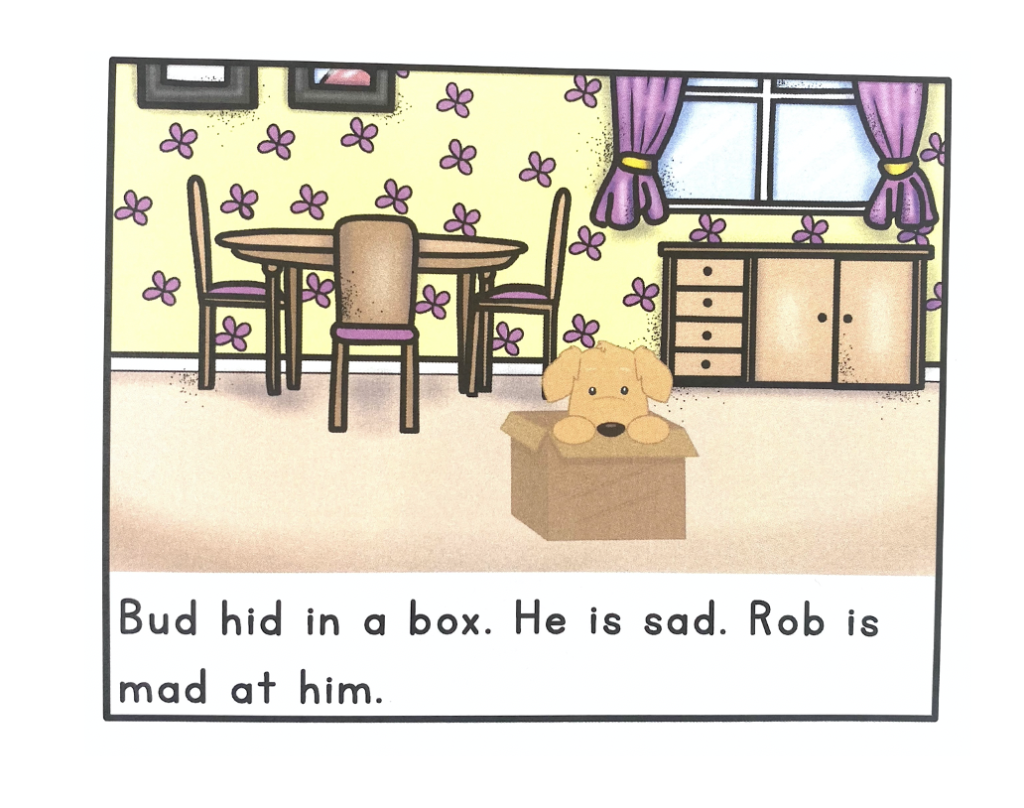

Unlike predictable or repetitive texts, decodable books are simple books written for beginning readers that encourage children to sound out words using decoding strategies rather than guessing words from pictures or predicting words based on other “cues.”

Proponents of “whole-language” instruction argue that learning to read is a natural process and that children will instinctively learn to read if they’re surrounded by books, similar to how humans learn to speak. But the scientific consensus is that whole-language instruction, as well as “balanced literacy” that is deeply rooted in whole language, are not as effective as a phonics-based approach.

Often, when students can’t read, there is enormous blame spread around—kids are blamed for not caring or trying hard enough, parents are blamed for not reading to their children or fostering a love of literature, or poverty is blamed for enacting barriers that some consider too challenging to overcome.

The root cause, however, is much simpler: even though research has demonstrated that it’s possible to teach almost all kids how to read by focusing on systematic, structured, and evidence-based reading instruction, many Minnesota schools and classrooms disregard the science and continue to utilize disproven methods to teach kids how to read.

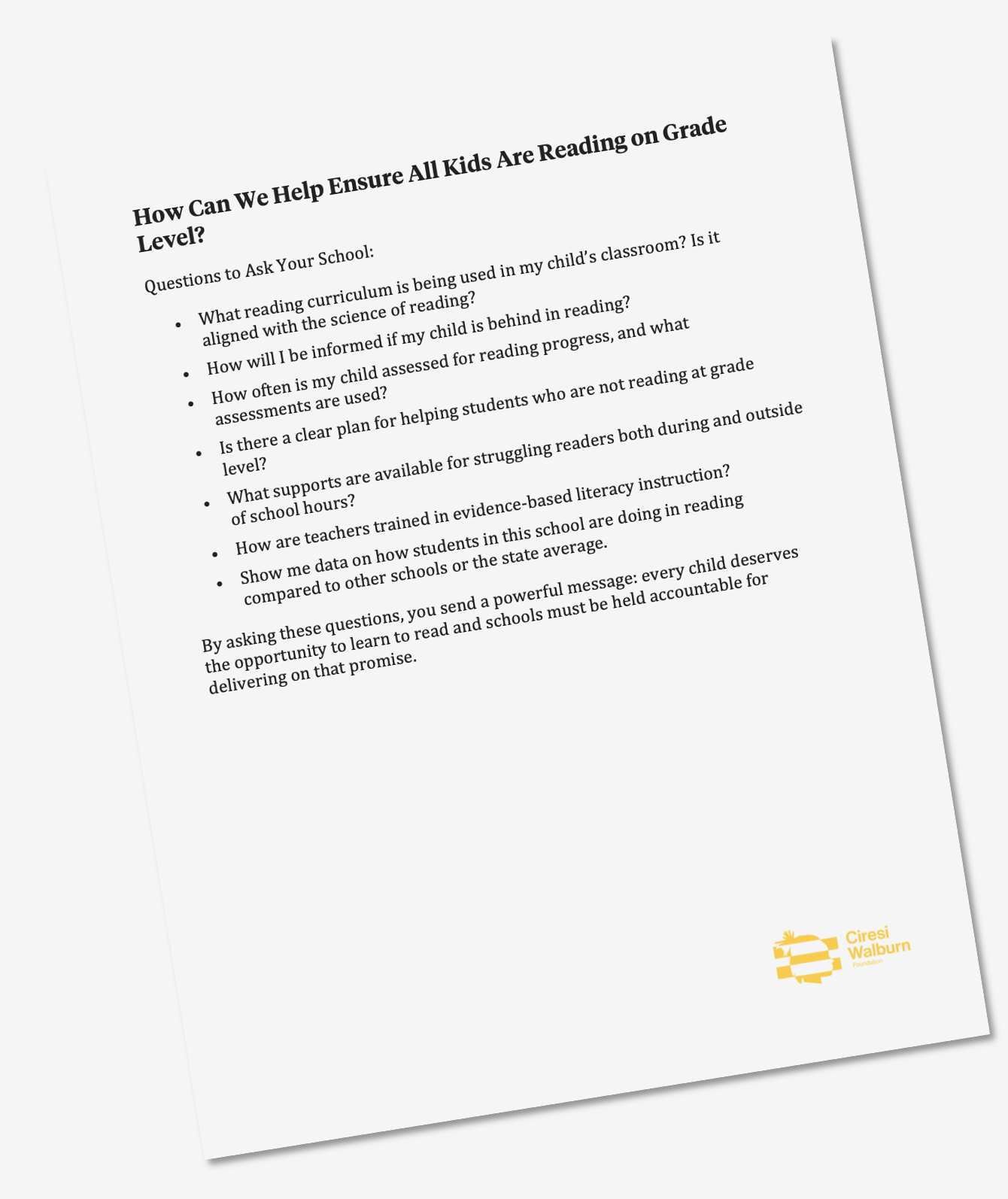

How Can We Help Ensure All Kids Are Reading on Grade Level?

Parent/Caregiver Download:

Parents and caregivers can click here to download a list of the questions to bring to parent/teacher conferences or their next meeting with school administrators.

What reading curriculum is being used in my child’s classroom? Is it aligned with the science of reading?

How are teachers trained in evidence-based literacy instruction?

How often is my child assessed for reading progress, and what assessments are used?

Is there a clear plan for helping students who are not reading at grade level?

How will I be informed if my child is behind in reading?

What supports are available for struggling readers both during and outside of school hours?

Show me data on how students in this school are doing in reading compared to other schools or the state average.

By asking these questions, you send a powerful message: every child deserves the opportunity to learn to read and schools must be held accountable for delivering on that promise.

Learn More

There's an idea about how children learn to read that's held sway in schools for more than a generation — even though it was proven wrong by cognitive scientists decades ago. Teaching methods based on this idea can make it harder for children to learn how to read. In this podcast, host Emily Hanford investigates the influential authors who promote this idea and the company that sells their work. It's an exposé of how educators came to believe in something that isn't true and are now reckoning with the consequences — children harmed, money wasted, an education system upended.

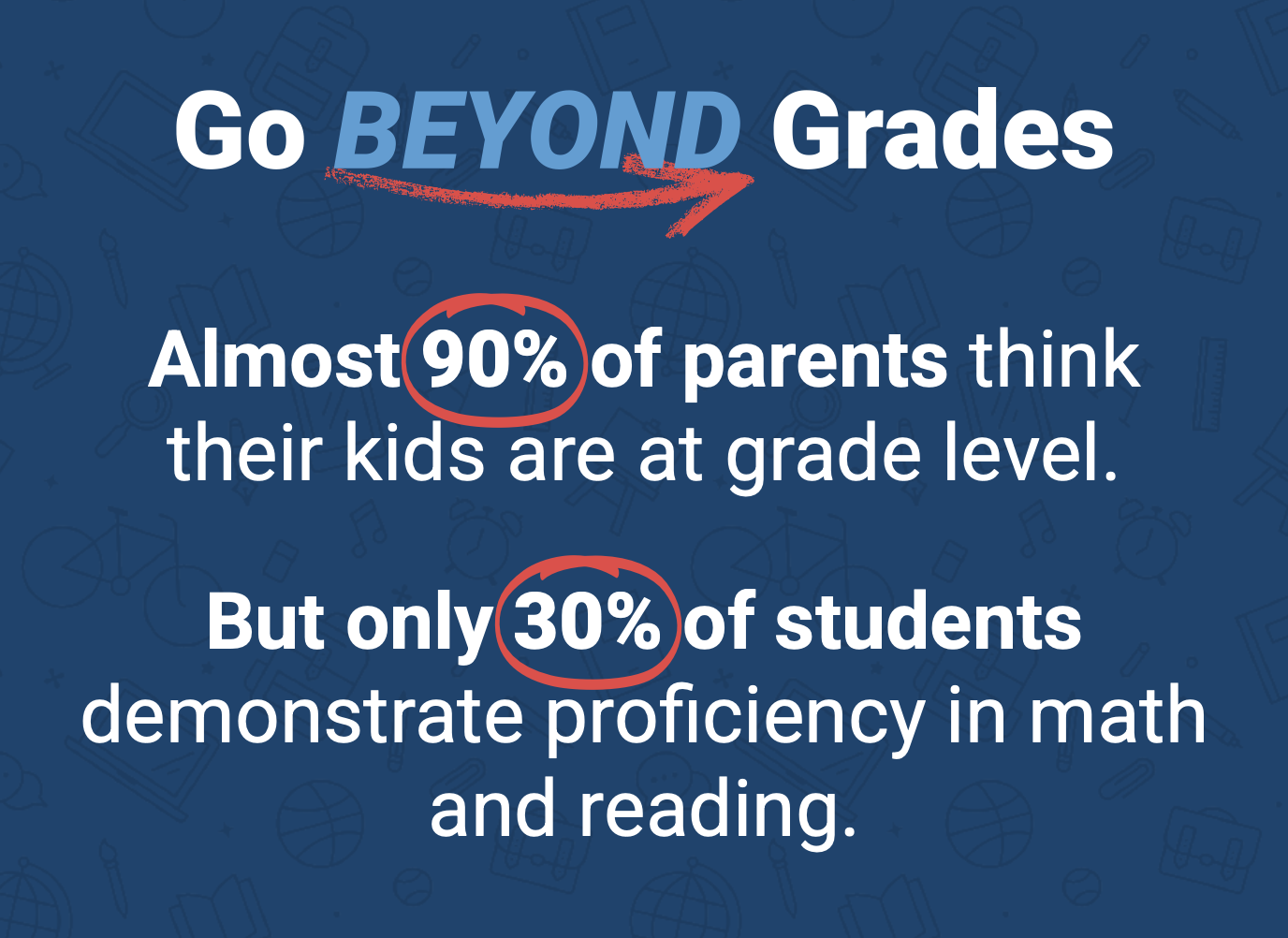

Learning Heroes partners with states, districts, and community-based organizations to engage families as a strategy for advancing school and student success goals. With their Go Beyond Grades campaign, they’re sounding an alarm.

Almost 9 in 10 parents nationally think their children are on grade level, despite a steady stream of data that tells a much more somber story of student achievement.

That’s why Learning Heroes wants to help parents go beyond grades. The site has free tips, tools, videos and more (in English and Spanish) to support families and teachers teaming up throughout the year.

The research and science are clear: We know how to teach kids to read. Explicit and consistent instruction in phonics and decoding is fundamental to developing skilled readers. Too many districts, schools, and classrooms across Minnesota are ignoring the science of reading and use “whole language” or “balanced literacy” English Language Arts (ELA) curriculums, which do not include nearly enough explicit phonics instruction to ensure all students become strong readers. So, why can’t little Sven and Helga read?